US Debt – When The Math Begins to Matter

What happens when the bond market stops playing along? Soaring debt costs and uneasy investors signal trouble ahead.

Executive Summary

For decades, warnings of a US government debt crisis have been more of a ritual than a reckoning.

Every period of fiscal excess has been met with rising voices of concern, only for the fears to dissipate as the world continued to accept the dollar. The argument has always been the same: as the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, the United States enjoys a privilege unlike any other nation. “We can always print the money,” some argue, “and the world will always take it.”

But what if that assumption is wrong?

What if the world’s tolerance for unlimited US debt isn’t infinite?

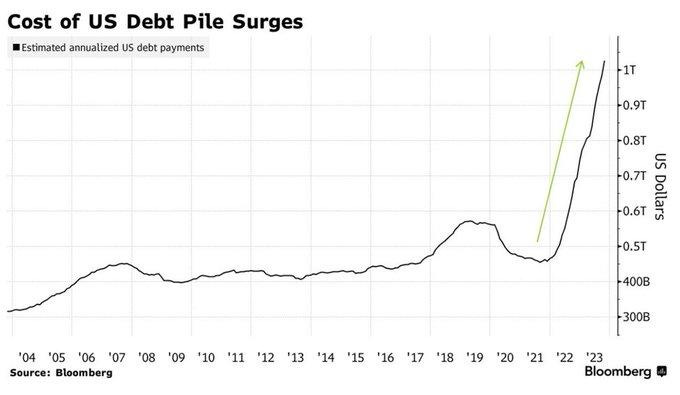

The numbers tell a troubling story. Debt servicing costs have quietly surged to become the second-largest item in the federal budget, despite interest rates that remain historically moderate. At less than 5.00%, the 10-year Treasury yield doesn’t appear punitive—but it doesn’t need to be for the math to become uncomfortable.

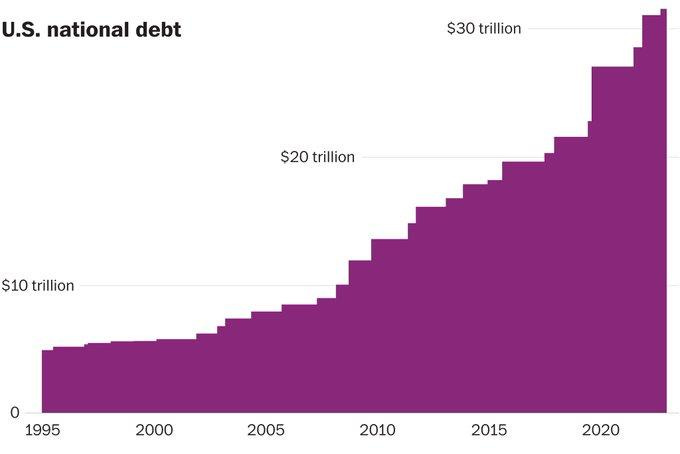

The great COVID fiscal expansion of 2020 was never reversed, and the trajectory of debt is now nearly exponential. Total government debt has soared from $20 trillion to $36 trillion in just four years—a staggering 80% increase.

Meanwhile, the deficit now sits at an annualized 6% of GDP—a peacetime record—and is growing by nearly $900 billion per quarter.

More troubling still is the short-sighted nature of US debt issuance. At a moment when the world was practically paying governments to borrow money, the US Treasury failed to act. The 10-year bond yield fell to 0.50%, presenting a once-in-a-lifetime chance to lock in ultra-low financing for decades, or even a century—an opportunity Austria seized when it issued a 100-year bond at just 2.1%.

Instead, the US kept rolling over short-term debt, a decision that is now proving catastrophic. One-third of all outstanding US debt matures in the next 12 months, exposing the government to the full force of rising interest rates.

But perhaps the most ominous signal isn’t coming from government balance sheets—it’s coming from the bond market itself. For the first time in history, long-term Treasury yields rose by more than 100 basis points after the Federal Reserve began cutting interest rates.

This isn’t supposed to happen.

Traditionally, when the Fed eases, bond yields fall. The fact that they didn’t suggests something more fundamental is shifting. The bond market—the lifeblood of the US financial system—seems to be growing uneasy.

Could we be nearing the moment when investors begin to question US creditworthiness in earnest?

Could there come a time when the world looks at America’s borrowing needs and simply says, “No”?

We aren’t making predictions, but history suggests that financial crises tend to emerge not in slow motion, but all at once. If trust in the US Treasury wavers, the implications will reach far beyond government finances. They will ripple through every asset class, every portfolio, and every economy tied to the dollar.

Perhaps the world will continue to absorb US debt indefinitely. Perhaps deficits truly don’t matter. But if those assumptions are wrong, we may soon find out that the most powerful force in finance isn’t a central bank, nor a government decree.

It’s the moment when the bond market stops cooperating.

Background

One of the largest conga lines in financial markets is that of forecasters predicting a US debt crisis. This line stretches back as far as 1971, when then-President Nixon effectively took the US dollar off the gold standard, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system that had governed international monetary policy since the end of World War II.

Under this system, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce, and other global currencies were pegged to the dollar. The arrangement relied on the credibility of the U.S. dollar as a stable, gold-backed currency.

However, by the late 1960s, the system came under strain as U.S. spending on the Vietnam War, domestic programs like the Great Society, and a growing trade deficit led to concerns that the U.S. did not have enough gold reserves to back its currency.

Foreign governments, particularly France, began exchanging their dollars for gold, creating a run on U.S. gold reserves. To prevent further depletion and protect U.S. economic interests, Nixon announced the suspension of dollar convertibility to gold, effectively transitioning the dollar and the global economy to a fiat currency system.

The removal of the gold standard had profound implications for global finance and U.S. fiscal policy. Without the gold standard as a constraint, the U.S. government gained greater flexibility to expand the money supply and incur debt. While this allowed for more dynamic responses to economic challenges, it also removed a key discipline on fiscal and monetary policy.

Economists, policymakers, and critics began to warn that the lack of a gold-backed currency would lead to unchecked government borrowing, inflation, and a potential debt crisis. The 1970s soon validated some of these concerns, as the U.S. experienced stagflation—a combination of high inflation, slow economic growth, and rising unemployment.

Then the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 further exacerbated inflationary pressures, and the Federal Reserve’s efforts to combat inflation with aggressive interest rate hikes led to economic volatility. Critics pointed to these developments as evidence that the post-gold-standard system allowed for irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies.

Forecasts of a U.S. debt crisis grew out of these fears, as many analysts argued that without the discipline of gold, the U.S. government could accumulate debt indefinitely. Some warned that excessive borrowing would devalue the dollar over time, erode international confidence in U.S. financial stability, and eventually lead to a collapse of the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

This reserve status, which provided the U.S. with unique advantages such as the ability to borrow cheaply and run persistent trade deficits, was seen as vulnerable if foreign governments and investors began to lose faith in the dollar’s long-term value. Such a loss of confidence, it was feared, could trigger capital flight, skyrocketing interest rates, and a full-blown fiscal crisis.

Over the decades, these concerns periodically resurfaced during periods of economic or political instability, as the U.S. debt has continued to grow. The absence of the gold standard has often been cited by fiscal conservatives and hard-money advocates as a root cause of America’s increasing debt burden, enabling policies that prioritize short-term economic stimulus over long-term fiscal responsibility.

While the feared collapse has not occurred—largely because of the dollar’s enduring role as the global reserve currency and the strength of the U.S. economy—the removal of the gold standard remains a key turning point in the history of U.S. fiscal policy, with its legacy shaping debates about debt, inflation, and the sustainability of government borrowing to this day.

Since the removal of the gold standard in 1971, numerous economic periods have triggered concerns about a U.S. debt crisis due to rising deficits, economic instability, or external pressures.

One of the earliest examples was the stagflation of the 1970s, when a combination of high inflation, stagnant economic growth, and soaring oil prices created economic turmoil. The fiscal environment of the time, marked by deficits stemming from Vietnam War spending and domestic programs, heightened fears that the U.S. government had lost fiscal discipline after abandoning the constraints of the gold standard.

Critics argued that the ability to print money without gold backing encouraged irresponsible borrowing and risked a loss of confidence in the U.S. dollar.

The 1980s marked another period of acute concern, as President Reagan's economic policies dramatically increased the national debt. Reagan’s administration cut taxes, increased military spending, and pursued deregulation, leading to ballooning deficits.

Between 1980 and 1989, the federal debt rose from $900 billion to $2.7 trillion, sparking fears that the U.S. was on an unsustainable fiscal path.

Economists warned that the combination of growing debt and high interest rates under Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker—who was combatting inflation—could lead to “crowding out,” where government borrowing competes with private investment, slowing economic growth. The growing debt also prompted worries about the U.S.’s ability to maintain confidence in its financial stability, especially as foreign nations like Japan became major holders of U.S. Treasury securities.

In the early 1990s, the national debt crossed $4 trillion, leading to widespread alarm about the country’s fiscal health.

This period saw a recession, rising entitlement spending, and persistent deficits. Bipartisan efforts like the 1990 Budget Enforcement Act under President George H.W. Bush and later fiscal reforms under President Clinton—including tax increases and spending cuts—were enacted to address these concerns.

By the late 1990s, these measures resulted in budget surpluses, temporarily easing fears of a debt crisis. However, the reprieve was short-lived.

In the 2000s, the U.S. entered another period of rising deficits. The post-9/11 era saw significant increases in military spending for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, coupled with President George W. Bush’s tax cuts in 2001 and 2003.

These policies contributed to growing deficits, which worsened during the 2008 financial crisis. The crisis itself led to unprecedented government interventions, including the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the $831 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programs.

By 2009, the national debt had surpassed $10 trillion. Critics argued that the rapid expansion of borrowing in response to the crisis could undermine the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and leave the U.S. vulnerable to a future debt crisis.

The 2010s brought renewed focus on debt with the rise of the Tea Party movement, which emerged in response to increased federal borrowing following the Great Recession. This period included the 2011 debt ceiling standoff between Congress and the Obama administration, which nearly resulted in a government default and led to the first-ever downgrade of the U.S. credit rating by Standard & Poor’s.

The national debt exceeded $15 trillion during this time, and political gridlock raised concerns about whether the U.S. government could enact necessary fiscal reforms. The debt ceiling standoffs in subsequent years, including those in 2013 and 2018, underscored the fragility of U.S. fiscal policy and the risks of political brinkmanship.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the 2020s brought the issue of U.S. debt to the forefront once again. Trillions of dollars were allocated for emergency relief measures, including direct payments to individuals, expanded unemployment benefits, and business loans under programs like the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

By 2022, the national debt had exceeded $30 trillion, and rising interest rates began increasing the cost of debt servicing. Economists warned that these trends could exacerbate long-standing concerns about entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, whose obligations were already projected to grow rapidly.

Some analysts feared that continued borrowing at this scale could erode the dollar’s global dominance, particularly as rival nations like China sought to promote alternatives to the dollar in international trade.

Other periods, such as the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and the Federal Reserve’s prolonged low-interest-rate policies after the 2008 crisis, also drew attention to the risks of debt accumulation.

While these concerns often did not materialize into immediate crises, they highlighted the structural challenges facing U.S. fiscal policy. Each of these periods demonstrates how shifts in economic conditions, global dynamics, and policy decisions have perpetuated fears of a U.S. debt crisis, underscoring the recurring and unresolved nature of these concerns.

The lesson of these examples for forecasters has been in being too early in predicting a debt-based US demise. Having the world’s sovereign currency has ameliorated any short-term risks of a debt crisis over and over, which has been largely ignored or discounted by such forecasters.

So, why would today be any different?

There are four reasons why today’s concerns about US government debt should be taken seriously:

The debt trajectory – government debt is increasing by around $1 trillion every quarter. The budget deficit, at around 6% of GDP, is at the highest non-recessionary level. This is unsustainable.

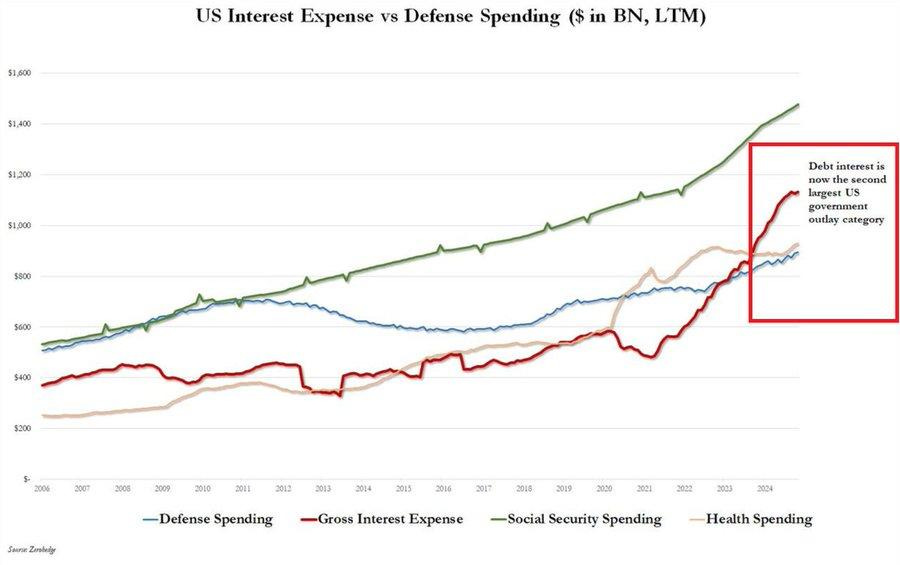

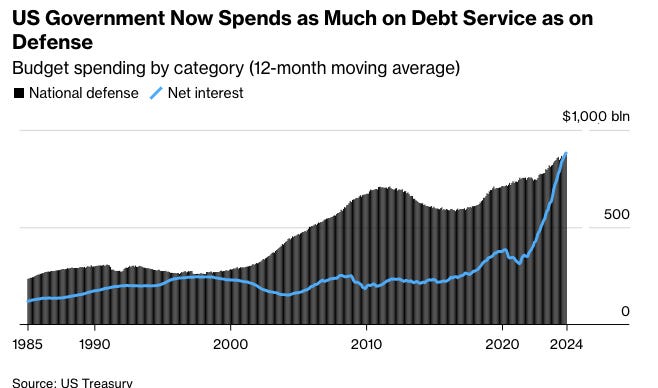

The interest cost – debt servicing costs are the second highest component of government expenditure.

The bond market appears unwilling to turn a blind eye to the above two points. Since the Federal Reserve commenced lowering interest rates a few months ago, the ten-year bond yield has risen by 120 basis points. This has never happened before in an easing environment.

The short-dated maturity profile – around one third of all US government debt matures within the next year. There is currently no buffer against structurally higher interest rates and/or inflation.

The Debt Trajectory

The rate of increase in US government debt has increased dramatically in recent years.

At the outbreak of Covid in 2020, debt was slightly more than $20 trillion. Today is over $36 trillion and increasing at a rate of nearly $1 trillion every quarter. That marks an 80% increase in government debt in the past five years.

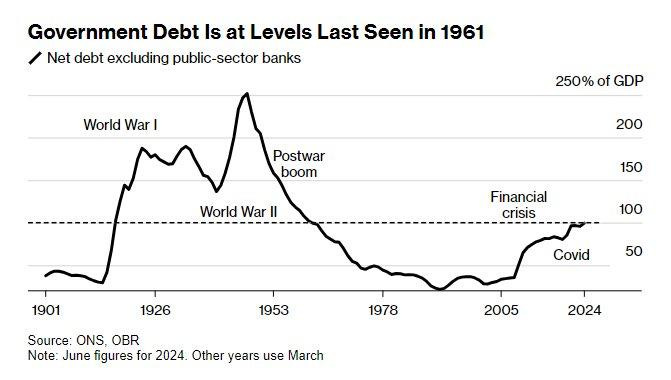

In terms of debt as a component of GDP, current levels are the highest since 1961:

With a platform of lower taxes, the incoming Trump administration hopes to reduce spending through a new Department of Government Efficiency. This sounds easy in theory, but according to Stephanie Pomboy, the total wage bill for the US government is around $800 billion.

With debt servicing costs now exceeding $1.1 trillion per annum, a very large number of government employees would need to be cut to make even a small impact.

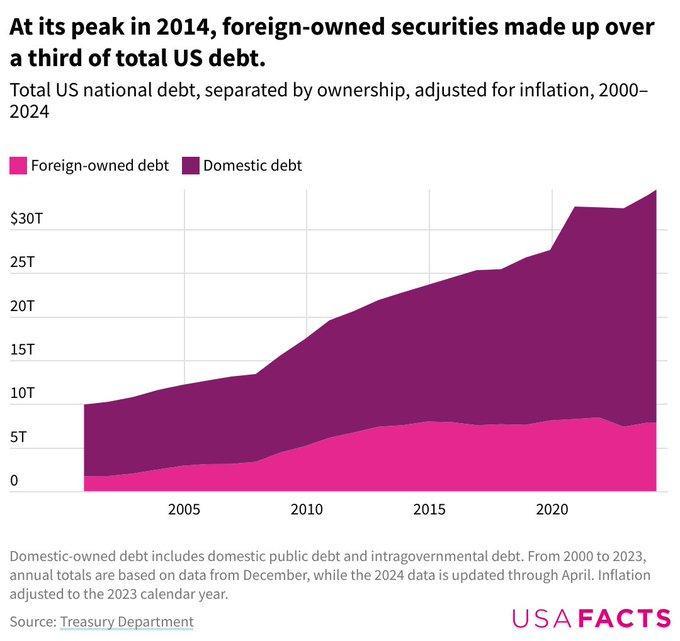

Furthermore, who is going to buy this increasing amount of debt?

The two largest holders, China and Japan, have been reducing their holdings in recent years. During that time, domestic buyers have accounted for the gap.

But for how much longer?

The long-term economic implications of the U.S. government’s $36 trillion debt are significant and multifaceted, with potential risks to growth, fiscal stability, and global financial markets. As the debt increases and interest rates rise, the cost of servicing the debt will consume an ever-larger portion of the federal budget.

This phenomenon, known as "crowding out," means government spending on debt servicing limits resources available for critical investments in infrastructure, education, research, and other areas that promote economic growth. Spending increasing amounts of the budget on debt servicing creates long-term pressure on sustainable economic growth.

Over time, this will erode the U.S.'s competitive edge and reduce productivity, leading to slower structural economic expansion.

High levels of debt also create vulnerability to economic shocks. In times of crisis, such as a recession or natural disaster, governments often rely on borrowing to finance stimulus measures or emergency relief.

However, with debt already at elevated levels, the U.S. may find it more difficult to respond effectively to future crises. This limited fiscal flexibility could prolong downturns and make recoveries slower and more painful. Additionally, the perception of unsustainable debt levels may lead to a loss of investor confidence, potentially causing a spike in borrowing costs during times of need.

The return investors seek for perceivably higher risks would add to the risk premium on US government bonds.

Another long-term consequence is the risk of reduced private investment. When the government borrows heavily, it competes with the private sector for capital, potentially driving up interest rates and making it more expensive for businesses to finance new projects.

This reduction in private investment can weaken economic growth over time, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where slower growth exacerbates the debt burden. Government expenditure is also inflationary.

Entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare are also key drivers of debt, and their growth could lead to intergenerational equity issues. As the aging population requires more spending on healthcare and pensions, younger generations may face higher taxes and reduced public services to cover these costs.

This dampens economic mobility and exacerbates income inequality, creating social and economic strains. Furthermore, uncertainty about future tax burdens and government spending priorities may discourage long-term planning and investment by businesses and households.

On a global scale, the sheer size of U.S. debt poses risks to the international financial system. If confidence in the U.S.’s fiscal management wanes, foreign investors and central banks may reduce their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities. A significant decline in demand for Treasuries would lead to a rapid increase in borrowing costs and potentially destabilize global financial markets.

While recent inflationary pressures have been attributed to supply chain disruptions and other short-term factors (“cost-push” inflation), persistent debt growth could lead to higher inflation in the future.

If the Federal Reserve were to monetize the debt—essentially financing government borrowing by creating money—it could undermine price stability, erode purchasing power, and destabilize the economy. High inflation would disproportionately harm low- and middle-income households, further widening economic disparities.

Addressing the debt problem often requires difficult policy decisions, such as raising taxes, cutting spending, or reforming entitlement programs. Governments can end up trapped. Reducing the unprecedented fiscal deficit in non-recessionary times would almost certainly lead to a recession. Such a recession would then require further fiscal stimulus, thus increasing the level of government debt.

Steep spending cuts would also reduce public investment in areas vital for long-term growth, while significant tax increases discourage innovation and entrepreneurship.

Efforts, therefore, to reduce debt could unintentionally exacerbate the very problems they aim to solve, creating a precarious economic environment for future generations and governments alike.

The Interest Cost

There are two important points to note about the following charts.

First, the budget deficit escalated in response to Covid. Keeping the US economy from effectively stalling during lockdowns saw unprecedented fiscal largesse.

Second, this largesse saw a resurgence in inflation, which led to higher interest rates, which then led to increasing debt servicing costs. Such servicing costs doubled in a matter of a few years.

Like the question of the sheer size of US debt, when does this reach a flashpoint?

If debt servicing costs were the second largest expenditure item in a third world economy, the risk premium demanded by investors would be very large. Being backed by the world’s sovereign currency is an advantage not held by such third world countries. But at some point, the sheer math will begin to matter.

We think that time is years, not decades, away.

And resolving such a crisis will have significant economic costs.

The U.S. government’s annual debt servicing cost, now exceeding $1 trillion, represents a growing challenge with potentially severe consequences for fiscal stability, economic growth, and intergenerational equity.

As interest rates rose after years of near-zero levels, the government is now spending more on interest payments than on critical federal programs like Medicaid and defense. On a gross interest basis, debt servicing is already significantly higher than defense spending:

On a net interest basis, debt servicing costs have caught up with defense spending:

This escalation in servicing costs highlights the vulnerability of a budget increasingly strained by rising debt and higher borrowing costs.

For decades, the U.S. has sidestepped concerns about its growing debt, relying on the dollar’s global dominance to maintain fiscal flexibility. But the numbers tell a different story.

With debt servicing now one of the largest government expenditures and the bond market showing signs of unease, the real question isn’t whether the U.S. can keep borrowing—but for how much longer?